Secflow: Unsupervised learning for analysis and detection of anomalies in Computer Networks

About this Article

This article was presented and published in the Extended Proceedings of the Brazilian Symposium on Information Security and Computational Systems (SBSeg23). The first author, Felipe Salles, won the award for the best scientific initiation presentation at the congress.

- Article link: https://sol.sbc.org.br/index.php/sbseg_estendido/article/view/27297

- DOI link: Link

Abstract

Anomaly and intrusion detection systems arise from the growing concern with network data security. Such systems need to identify anomalies in network traffic. Characterizing the anomaly types allows us to identify vulnerabilities and propose strategies to mitigate attacks. This research proposes network traffic analysis methods for detecting anomalies through unsupervised learning. When applied to a sliding window, this model aims to classify flows in an active network to identify different types of traffic anomalies. The model developed in this work will be applied to the production network at Universidade Federal Fluminense.

Introduction

The increasing number of end systems on networks has contributed to the exchange of information between these devices, presenting risks to user security. Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) are used to detect possible attacks in the Computer Network environment. There are two types of IDS systems: signature-based and anomaly-based.

Although signature-based IDS systems are widely used, they have some limitations, such as requiring prior knowledge of the attack to create accurate signatures and the possibility of false alarms when non-attack traffic matches a dataset signature [bay_mining_2003]. On the other hand, an anomaly-based IDS creates a traffic profile while observing traffic in normal operation. It looks for packet flows that are statistically unusual, such as an irregular percentage of ICMP packets or exponential growth from port analyses and ping scans. Although this system also suffers from the issue of false alarms, an advantage is that it does not rely on prior knowledge of other attacks; that is, it has the potential to detect attacks that have not been documented [kurose_computer_2017].

Having an IDS system is mandatory to protect critical networks. However, it is difficult to obtain a suitable dataset to evaluate the developed system [sharafaldin_developing_2019]. In general, available datasets are out of date with current attack trends and suffer from a lack of attack diversity in the traffic classification process [su_hierarchical_2018]. In this context, systems based on flow analysis are more suitable for monitoring a network, as they analyze the network traffic in operation [hofstede_flow_2014].

In this research, we chose to initially acquire knowledge of the problem domain by adopting a simple approach to identify anomalies [yang_neighbor-based_2009]. We used the DBSCAN clustering algorithm as a method, which clusters data based on similarity and identifies outliers as anomalies. Our results show that DBSCAN is capable of obtaining good accuracy. However, it does not identify a satisfactory proportion of attacks (high rate of false negatives). Our preliminary results suggest using more complex anomaly detection algorithms, such as collective anomaly detection [wang_network_2022], to identify attacks.

The ultimate objective of this research project is to develop an IDS system to evaluate network traffic at Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF). Furthermore, we intend to provide important information so that responsible sectors can implement more policies to mitigate attacks that are commonly propagated on the university network.

Method

In this research, we adopted a continuous Clustering approach using a sliding window in order to simulate the analysis of continuous network traffic. The unsupervised approach (Clustering) is advantageous for detecting anomalies without having to previously classify the data [mirsky_anomaly_2017]. We initially chose to apply the DBSCAN algorithm, as it is a technique that identifies anomalies (outliers) directly due to its density-based clustering approach. We believe that tests with different algorithms and techniques need to be done to evaluate which algorithms can provide better results to identify attacks in network traffic.

Database

At this stage of the research, we evaluate the approach using the public database UNSW-NB15 [moustafa_unsw-nb15_2015]. This database has a hybrid set of normal records (2,218,761) and nine categories of attacks, namely: Fuzzers (24,246), Analysis (2,677), Backdoors (2,329), DoS (16,353), Exploits (44,525), Generic (215,481), Reconnaissance (13,987), Shellcode (1,511) and Worms (174) collected from normal traffic [moustafa_evaluation_2016, moustafa_novel_2019]..

Pre-Processing

The data pre-processing step of the UNSW-NB-15 set was started by extracting 20% of the data (approximately 50,000 flows) for each label, including normal and anomaly (attack) records. We carry out Z-Score standardization to eliminate the influence of dimension between features and to guarantee the adjustment of each feature to the normal distribution.

We use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to make a selection of variables. Variable selection reduces redundancy in information, in addition to reducing complexity and computational cost. Some examples of features we selected are: (transaction protocol, port number, duration, bytes, packet count, TCP sequence number, packet arrival time, and recording start time). The most relevant features in the First Principal Component were selected, adopting a threshold of 0.05. 36 of the 49 features present in UNSW-NB15 were selected.

DBSCAN with Sliding Window

DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) is a clustering algorithm that is based on the density of points to identify clusters in data sets. The algorithm uses two main parameters: the neighborhood radius (epsilon), which defines the maximum distance for a point to be considered its neighbor, and the minimum number of points (minutes), which determines the minimum number of points in the neighborhood so that a point is considered a central point. The central points, together with neighboring points, form a cluster.

The decision to use DBSCAN came from the idea that this algorithm can classify points that do not meet the minimum density criteria, calling them anomalies. These points may be isolated, or they may be in low-density positions that are insufficient to form a cluster. We apply DBSCAN to our dataset in a sliding window of size 1000 and a sliding value of 10. In each window, we apply DBSCAN to identify anomalies that can be characterized as attacks in our dataset. Adjusting the DBSCAN parameters is extremely important to obtain satisfactory results, and we evaluate our model using the following values: (epsilon = 1.5 and minPts = 2), (epsilon = 0.95 and minPts = 2), (epsilon = 1.5 and minPts = 5) and (epsilon = 3 and minPts = 10).

Assessment Metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of the DBSCAN algorithm in detecting anomalies in computer networks, we calculated the metrics True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), True Negatives (TN), and False Negatives (FN) to evaluate the performance of the algorithm in relation to the correct classification of data.

To measure the detection effectiveness, we calculate the accuracy for each analyzed window. This metric is obtained by dividing the total number of correctly classified instances (TP and TN) by the total number of evaluated instances (TP, TN, FP, and FN) in each window. We report the average accuracy obtained across all windows. We also present a confusion matrix reporting the average of the TP, TN, FP, and FN values obtained in each window for each combination of DBSCAN parameters.

Preliminary results

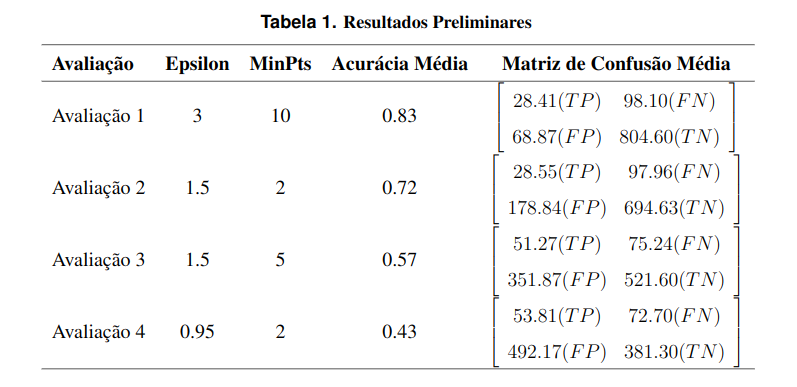

Analyzing anomalies in computer networks using the DBSCAN approach allows us to evaluate the sensitivity of the algorithm to different parameter values. In this section, we present the results obtained from this analysis (Table 1), demonstrating the values of the parameters we used, the respective total average accuracy rates of the windows, and the average confusion matrix for the respective parameters used.

Analyzing the results presented in Table 1, we observed that the parameter configurations that presented a good average accuracy did not achieve a good attack success rate. This disparity is attributed to the imbalance of the classes since the number of normal samples is greater than those of attacks. As our main interest is to identify attacks, we tested other parameter settings. Among the parameters explored, the configuration that best identifies attacks (TP) obtained 53 TP with 72 FN per window, which would still fail to identify more than 50% of attacks. This configuration results in a high FP rate that can degrade system performance and increase flow analysis overhead. Higher values of epsilon increase accuracy, as normal flows, are correctly grouped into clusters; however, several attack flows also end up being grouped and are not identified as anomalies. Small values of epsilon increase the detection of attacks as anomalies but reduce accuracy by not grouping together several normal flows that will be identified as anomalies.

Discussion

The objective of this study is to develop a network monitoring method capable of evaluating flows in real-time and identifying possible attacks. Initially, we chose to identify attacks using a simple clustering algorithm capable of detecting anomalies. Aiming at the final monitoring system, we chose a sliding window approach capable of evaluating new flows together with already evaluated flows. As the types of flows contained in a window can vary, we do not know in advance how many clusters we expect to obtain. Therefore, we chose the DBSCAN algorithm, which does not require prior determination of the number of clusters. When varying the DBSCAN parameters, we noticed that a higher epsilon increases accuracy due to the correct classification of TN. However, there is an increase in FN. A lower epsilon value increases the amount of TP but decreases the TN, resulting in lower accuracy. Based on the preliminary results obtained, we conclude that individually evaluating flows as anomalies within the sliding window is not a suitable strategy for identifying attacks in a network.

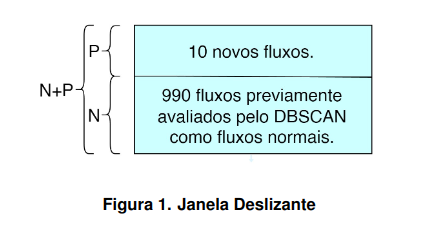

In the next phase of the project, we will use the same methods already mentioned for pre-processing, feature selection, and clustering. However, we will use a collective anomaly detection strategy [wang_network_2022]. For each analyzed set, we will check if there is any flow that is an attack without classifying the flows individually. We start with a window N containing 990 flows that do not show anomalies after DBSCAN clustering. A smaller window P receives 10 new flows. The window to be clustered (Figure 1) is formed by N + P (1000 flows). We assume that flows in N are all normal, so if DBSCAN identifies an anomaly, the possible attack is in window P. We report these 10 flows from P to be analyzed by the network administrator. In this way, we increase the probability of identifying a set of flows that contain an attack on the network, as we capture anomalous patterns and behaviors that may not be evident when analyzing each flow individually. The idea is to reduce the amount of data that the network administrator needs to analyze, maximizing the chance that attacks are among the reported flows.

We aim to apply our approach to network traffic at Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) to obtain a characterization of the attacks suffered and mitigate attacks that are commonly propagated. We also intend to contribute with new improvements to existing anomaly detection approaches. Although we do not yet have all the answers, this analysis provides a solid basis for future investigations, raising questions that will be explored in the next stages of research.

Conclusion

This article proposed to carry out a preliminary study of network monitoring through the identification of anomalies applying the DBSCAN algorithm. The results show that this approach did not achieve the desired level of performance in identifying attacks. Therefore, there is a need to seek more effective methodologies to solve the problem. Therefore, in the next stage of this project, we intend to develop the collective anomaly identification approach described in section 4.

We will explore new methodologies for detecting attacks, seeking to identify attacks (TP) more efficiently and present better results than those achieved with the initial approach adopted. This article represents just the first step toward efficiently detecting attacks in computer network traffic.

DOI

DOI link: Link

References

Bay, S. D. and Schwabacher, M. (2003). Mining distance-based outliers in near lineartime with randomization and a simple pruning rule. InProceedings of the ninth ACMSIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining, KDD’03, pages 29–38, New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Hofstede, R.,ˇCeleda, P., Trammell, B., Drago, I., Sadre, R., Sperotto, A., and Pras, A.(2014). Flow Monitoring Explained: From Packet Capture to Data Analysis WithNetFlow and IPFIX.IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 16(4):2037–2064.

Kurose, J. F. and Ross, K. W. (2017).Computer Networking: A Top-down Approach.Pearson.

Mirsky, Y., Shabtai, A., Shapira, B., Elovici, Y., and Rokach, L. (2017). Anomaly detec-tion for smartphone data streams.Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 35:83–107.

Moustafa, N. and Slay, J. (2015). UNSW-NB15: a comprehensive data set for networkintrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set). In2015 Military Com-munications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS), pages 1–6.

Moustafa, N. and Slay, J. (2016). The evaluation of Network Anomaly Detection Systems:Statistical analysis of the UNSW-NB15 data set and the comparison with the KDD99data set.Information Security Journal: A Global Perspective, 25(1-3):18–31.

Moustafa, N., Slay, J., and Creech, G. (2019). Novel Geometric Area Analysis Techniquefor Anomaly Detection Using Trapezoidal Area Estimation on Large-Scale Networks.IEEE Transactions on Big Data, 5(4):481–494.

Sharafaldin, I., Lashkari, A. H., Hakak, S., and Ghorbani, A. A. (2019). DevelopingRealistic Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attack Dataset and Taxonomy. In 2019 International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology (ICCST), pages 1–8.ISSN: 2153-0742.

Su, L., Yao, Y., Li, N., Liu, J., Lu, Z., and Liu, B. (2018). Hierarchical Clustering BasedNetwork Traffic Data Reduction for Improving Suspicious Flow Detection. In 2018 17th IEEE International Conference On Trust, Security And Privacy In ComputingAnd Communications/ 12th IEEE International Conference On Big Data Science And Engineering (TrustCom/BigDataSE), pages 744–753. ISSN: 2324-9013.

Wang, C., Zhou, H., Hao, Z., Hu, S., Li, J., Zhang, X., Jiang, B., and Chen, X. (2022).Network traffic analysis over clustering-based collective anomaly detection.ComputerNetworks, 205:108760.

Yang, D., Rundensteiner, E. A., and Ward, M. O. (2009). Neighbor-based pattern detec-tion for windows over streaming data. InProceedings of the 12th International Confe-rence on Extending Database Technology: Advances in Database Technology, EDBT’09, pages 529–540, New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery.